STOPPING MASS SHOOTINGS (Part 5)

by Brendan Steidle

Detection, Preparation & Spaces

All this time, we’ve been talking about shooters who shoot for reasons of fame and notoriety. Shooters who plan their shooting. Meticulous. Careful. Committed enough to take trips across the country to learn more about their shooting heroes. But what about shooters who shoot reflexively? The angry spouse who goes on a rampage? Or the factory worker who’s just been fired? What can we do to stop the shooter who first thinks to shoot on the day of the shooting itself?

This is hard to prevent—because the less time there is between the first step of planning and the last step of shooting, the less time we have to get between those two steps and stop it. But even day-of shootings have their warnings—even if the first warning is warned with a bang. The first shot fired. Did you know that before two of the three deadliest shootings—those outliers on our graph—there was a first shot fired somewhere else? A first shot fired either miles or hours before? In the Virginia Tech Shooting, the shooter—a student—killed someone in his dorm room early in the morning. The dorm was on campus, the shooter was loose—but notification never made it out in time.

And so the students—all the while the shooter was planning his shooting, stalking the campus—the students woke up that morning, clutched coffee, packed their bags and ascended the stairs to their second floor classroom. They chatted and milled about before the professor arrived. They exchanged friendly hellos—all the while police knew there had been a shooting on campus. All the while this spinning vortex of a shooter spun towards them. And it was a few minutes later—while they sat in their classroom learning French… hours after the first shot was fired—that the first notification was sent. By email. In an age before smartphones. But it was too late. The shooter was already in the building. The exits chained shut. What the hell?! The campus knew. And nothing was done. The police knew—and nobody was saved. So—here’s an idea: let’s do something when there’s a shooting nearby. Let’s treat shooters like tornadoes. The moment a shot is fired, you batten down the hatches.

Classes are suspended. Businesses shut down. And extra security floods in. Those classes on that day should have been cancelled—the university should have shut down. There was an active shooter at large. Someone had already been killed. This didn’t have to happen. 32 lives lost.

But we can take this even further. Because ‘nearby’ isn’t near enough. The shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary—that one didn’t start at Sandy Hook, either. It started at home, as so many shootings start. But it crept out from there—like a flame climbing up the branches of a tree. The distance between the home and the school at Sandy Hook—5 miles. You have to take Riverside Rd, make a right onto Philo Curtis Rd., turn left onto Jeremiah Rd., then a right onto Bennetts Bridge, a left on Bresson Farm Rd., and then—well…you get the idea. It’s not a straight line. But you can draw a straight line from the shooter to the target: Sandy Hook is where the shooter’s mother worked.

It’s not, enough, then—to batten down the hatches nearby. We have to get those schools and workplaces that are connected to the killer to batten down their hatches, too.

Because shooting after mass-shooting, one thing emerges: public mass shootings often start in private. When a boyfriend, spouse, or family member turns violent. That violence at home then spills over into the workplace, school, or other public space. The moment a shooting is registered in private and the shooter is at large, a warning should be sent out to every institution that may be a potential target. The shooter’s place of business? Yes. Place of learning? Yes. Place of worship? Double-yes. The warning can instruct the institution to shut down, evacuate, or simply go on security alert.

How do we achieve this? Social media integration. Social media has already mapped all of these connections for us—every branching tendril of social networks. In fact, that’s what social networks are—networks. So if one node in that network goes berserk, those around that network—close by relationship but not necessarily proximity—should be alerted. Family. Friends. Coworkers. And—importantly—coworkers of family. There are already online systems that capture real-time police-scanner data. We only need social networks to integrate this information into their “social graph” in order to send out warnings and safety announcements. In time, of course, for people to do something about it.

Okay—so this helps prevent day-of shootings that start at the home. But what about those shootings that begin at work? Well, we know that most workplace shootings have a trigger—and we know what that trigger is: firings and suspensions. Sixty percent of all shootings at factory workplaces were the direct result of a firing. Take the case of the Nu-Wood Decorative Millwork Plant in Goshen, Indiana. When a 36 year old was fired in December of 2001, he left the facility and then—later that day, returned with a gun. He shot seven of his co-workers, wounding six and killing one before turning the gun on himself. Now, some companies know that firings can be sensitive—so they have security escort an employee off the premises. But that wouldn’t have worked here, would it? Because after the escort, he would have just come back with his gun. Coming back is an issue. It isn’t just an edge case. It happens all the time: someone is fired or suspended, they leave work, and before the day is up they return to target their coworkers.

The answer? How about simply working the calendar a bit here? How about pushing these companies to adopt a new best practice: only fire or suspend workers after all others have safely left the premises? This could mean saving it until after hours, or letting all workers leave early. Or—yes—walking the individual out with armed security, but then also posting armed security at the doors for a week or two after the firing. If that’s too expensive to do for every single firing, then companies can batch firings and suspensions together. But something as simple as this—having some sort of strategy and timeline for firings and suspensions, scheduling them off-hours and using basic security best practices, can save lives. If factories had these policies in place over the last 15 years, we could have saved 30 lives.

Detecting the First Shot

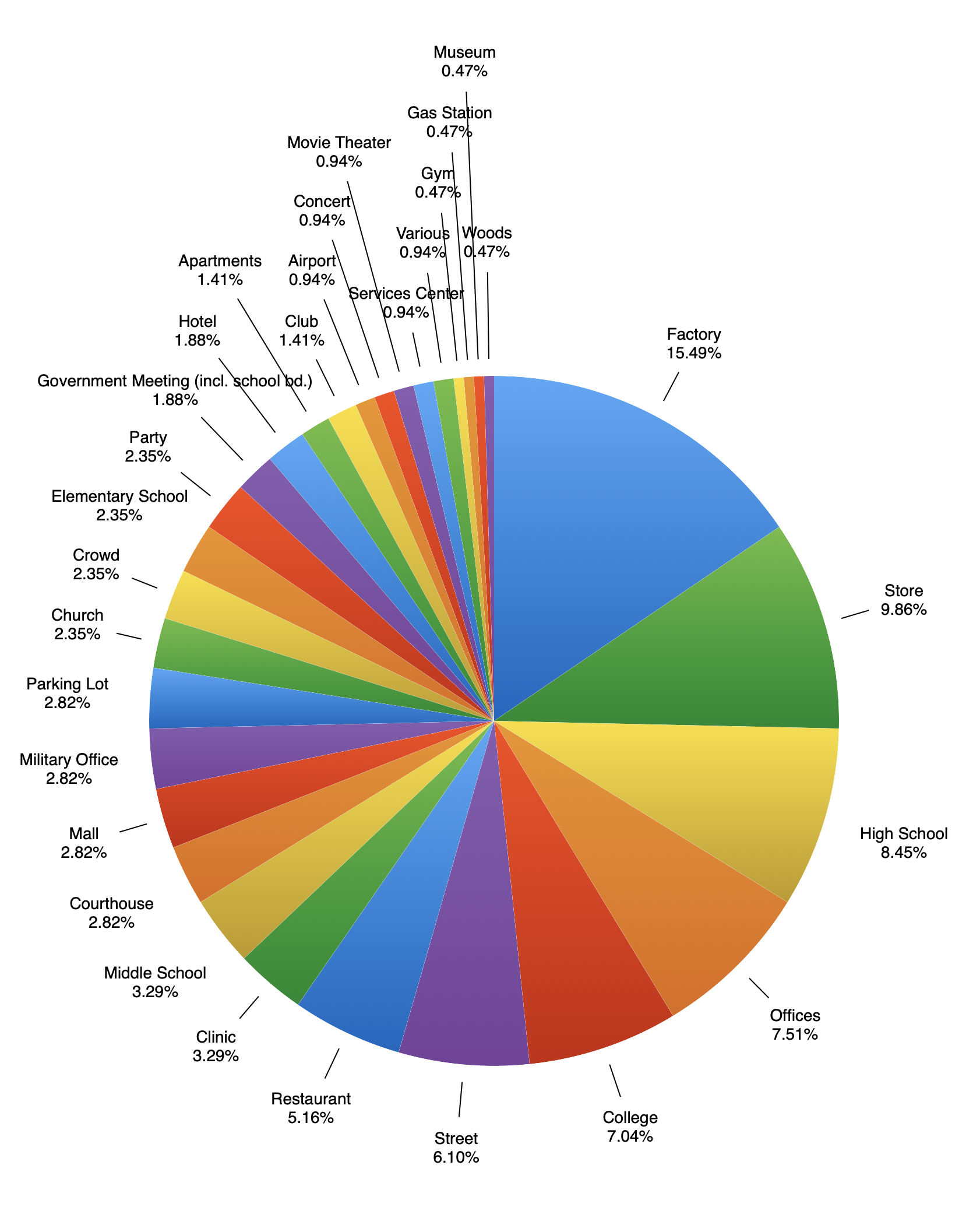

But—I hear you saying. But what about shootings that take place anyway? Ones that fall through the cracks of all of these efforts at reduction? Or—what about that swath of shootings that take place in broad public arenas—like stores, crowds, and the street? Stores are the second most likely location for a shooting to take place—and a surprising number of active shooter incidents take place on the street. When an assailant begins randomly shooting as he walks from block to block—rounding corners where unsuspecting pedestrians are caught off guard.

What can we do to save lives? Well, this exact problem faced the cities of Europe during World War I. Because there was a new threat: aircraft. Silence. Stillness. And then: A screaming comes across the sky. Weapons considerably more terrifying than anything known before.

When a dull roar filled the air in the small coastal British town of Great Yarmouth in the cold of January, 1915, nobody knew what it was. Until the streets of the tiny hamlet exploded. The city had become the first victim of a new campaign by Germany—to target civilians in the British countryside. A new campaign and a new kind of warship. The Zeppelin. A massive ship with tons of capacity for bombs: 536 ft long and 61 ft in diameter. It could travel as fast as 85 miles an hour in a time when the fastest battleships could only travel around 30 miles an hour. And they would attack in the dead and darkness of night—under cover of the clouds.

A new technology was invented in turn: called “war tubas.”

They looked ridiculous—but their principle purpose was serious. To listen for the tell-tale frequency of an aircraft engine. There had been nothing like this before. Because as aircraft grew in power and precision, so too did these listening devices. The British began setting up permanent, “acoustic mirrors”—15 ft tall monoliths of concrete. They’d be installed in three pieces, with microphones at the focal point. Designed to triangulate a sound far across the English Channel. So that as soon as an aircraft began its journey towards Britain, the early warning systems would light up across the coast. And defenses drawn.

The technology has gone a long way from there—beginning about 25 years ago they started mounting this technology in cities to cut down on crime. It’s estimated that in some particularly rough neighborhoods only about a quarter of all of the gunshots fired are ever reported. With specially-tuned microphones mounted around town, first responders are able not only to detect gunfire—but actually to triangulate its location. Down the exact address. Sending in police and ambulances to stop the violence and rescue victims who may already be bleeding.

Now, nearly every major city in America has gunshot listening devices. Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia. Washington, D.C. alone said in 2008 it helped them save 62 victims and led to 9 arrests. Today’s technology uses state of the art neural networks to distinguish gunshots from other loud noises like fireworks, backfiring cars, and falling pianos. But the key—of course—is the same as it’s always been: war tubas. Yes, microphones.

Even the microphones in phones are pretty great. They might not be studio quality—but movie studios are taking note. In the Oscar-winning film Selma, David Oyelowo actually recorded some of his voice-over work as Martin Luther King, Jr. with an iPhone.

So…what if every phone had the capability to detect a gunshot? And the moment it did—a warning was instantly sent out to other phones in the area—to warn people of the danger?

Just imagine it—a gun is fired; the bullet rips through the air, breaking the sound barrier. And between the pop of the muzzle and the snap of the air, phones nearby register it—their microprocessors spark at 600 billion operations a second, sending at the speed of light a warning to other devices in the immediate vicinity. So that before the sound of the first bullet reaches the ears of the person in the next room, their phone is already pinging. The tech can work using wifi and bluetooth for instant signaling to phones nearby—so it works even if you have a spotty signal. The range of Bluetooth 5.0 is now 800 feet. So there’s plenty of time to seek cover. Imagine if, using the gyroscope, compass, and GPS built into every phone already—you could see a red arrow pointing in the direction of the gunshot.

But how would the phone know the direction if it’s just one phone? Well—because if every phone has this technology, the phones can talk to each-other. And just as multiple detectors work to triangulate gunshots in a city, multiple phones can triangulate the location of a gunshot. Pinpoint it—and broadcast that location to every phone in the area.

How big is this area? Well, it can extend beyond the range of WiFi and Bluetooth—of course. If there’s a cell-signal, the warning can be sent out to everyone within a mile of the shot. And it can also auto-generate a message to be sent to local police and first responders.

This might sound like science fiction, but if you can use your phone to catch an Uber, we can use our phones to dodge bullets. A paper by David Welsh and Nirmalya Roy of the Information Systems Department at the University of Maryland tested the accuracy of using smartphones as mobile gunshot detection systems. Rather than just using the microphone, they combined the microphone with every other sensor in the phone:

Microphone

Accelerometer

Gravity

Gyroscope

Light Sensor

Linear Acceleration

Magnetic Field

Orientation

Pressure

Proximity

“Not only can gunshots be detected, but the sensors are able to capture enough unique data to accurately classify them,” they wrote. When they combined all of the sensor data from a single phone, the classification accuracy reached 99.6% for both slow and fast shooting instances. With multiple phones networked together, the accuracy would be a virtual certainty. And that’s without any changes to phone hardware at all.

The technology is already there—all of it. The microphones, the gyroscopes, the networking and radios. All we need is a handful of companies to get onboard—Apple, Google, Samsung, LG. Just create a partnership, a consortium aimed at saving lives. And believe me—we’d save lives:

Those 77 people killed in open spaces. The next 77 might be saved. The 20 people killed in stores. The next 20 people might be saved. And the next and the next. We can draw down the death toll on nearly every type of mass public shooting. But you know what? It wouldn’t stop there; because victims of other types of gun violence could also have a fighting chance. Imagine people who get shot in other instances, for other reasons, in other types of violence getting the warning. And not only that—imagine that this warning is also sent to first responders. So that those first responders can get to the victims to help them immediately.

And the perpetrators—well, they’ll have less of a chance of getting away with it.

Now—there might be a few objections.

What if the shooter turns off his phone? No problem. Because those being shot won’t have their phones turned off.

What if you’re at a gun range, or a place where it’s perfectly fine to be firing a gun? No problem—just turn off your phone’s detection system for an hour, two hours—a day even. But after a certain period, it turns back on. By default. Places like gun ranges can also have their geo-location pre-marked so that phones in those geofenced areas are trained not to send false alarms.

What if you get a message that there was a shot a mile away—and what if you get these messages all the time. Won’t it freak you out—causing insecurity and a deep-seated fear for their own neighborhoods? Well, we can build a messaging system into the framework, so that after first responders have checked out the scene, an update message is sent to all users who received the warning. Giving them a sentence or two of detail and assuring them it’s all clear.

Just imagine what a system like this could do to reduce gun casualties. And it’s all right there, the technology is in your pocket.

Personal Defense

What happens after that first shot is fired? What can we do, then? Well, if a shooting is taking place, one way to reduce the number of casualties is to make sure the people under attack are prepared. What should you do when it’s taking place? When should you run? When should you stay and try to warn others? Where and how should you hide? And when is it the best option to fight back? These are all really important questions—and there are best-practices out there for dealing with them. But many people don’t know the answer—many are unprepared for such an incident.

Slowly, that’s changing. The FBI has developed video training to help prepare people for what to do. Large companies, universities, and other places of learning are beginning to make the video standard viewing. Hundreds of thousands of students every year are being run through training programs. Just as instructions before your flight can prepare you for the unlikely event of a plane crash, video instructions can help people prepare for the unlikely event of an active shooter attack. At the time of this writing, it’s actually more likely to be in an active shooter incident than for your commercial airplane to go down.

According to a recent study published in the Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, college students who saw an active shooter preparedness video felt on average about 30% more prepared for an incident. But the video did increase fear by about the same amount. The effect was greatest on female participants—who felt nearly twice as prepared after watching the video, but 30 percent more fearful. The research authors suggest that a less graphic video and less graphic training might be more effective in preparing students and assuaging fear. After all, some schools go as far as staging active shooter training drills—complete with student actors, toy guns and fake blood. As they noted:

“There is a reason that airlines do not routinely run passengers through simulations of a plane crash, or have them watch videos of screaming passengers putting on oxygen masks as their plane goes down. The risk of a plane crash is so minimal that it doesn’t warrant that level of emotional trauma. It invokes feelings of terror that would make no one want to ride on a plane again.”

—The Journal of Threat Assessment & Management

We could take a cue from the training videos of airlines—which are getting more stylized and less frightful by the day.

So how about this—we engage young filmmakers to develop creative approaches to active shooter safety. Make it a rite of passage—for aspiring directors, producers, and actors to get together and develop a visually-compelling, engaging, and ultimately thoughtful video. Just as every young actor learns a Shakespeare monologue, every pianist learn how to play Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata—every filmmaker can create one of these public service announcements. Have a contest or awards program each year to judge favorites—some animated, some in sign-language, or performed by mimes—some done through magic, others performed onstage—an endless stream of potential videos for educators, businesses, and organizations to choose from. And every so often, a video that goes viral and launches a new career. The goal here isn’t to make light of active shootings—of victims or of the danger; it’s to reach people in an effective way: to prepare them, but not to scare them.

Preparation doesn’t stop at education. Part of it is also preparing people to fight back when possible. It’s a maddening cliche at this point: the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun. But it’s true that in some instances, guns have stopped active shooter incidents. But so has pepper spray, a piece of furniture, or simply a shouted command. So maybe part of preventing active shooter incidents is to make tools like pepper guns as common as fire extinguishers. In fact, you could put them in the same places you find fire extinguishers—in every classroom, at least every hallway. So that the moment shots are fired, people are ready to “break the glass” and take down the shooter. Pepper guns are a great option here, since they are non-lethal and don’t even have any long-term side effects—but they can incapacitate a shooter. Even better—by putting them behind the same glass as fire extinguishers, we can rig them with alarms that sound whenever that glass is broken. Alerting others outside of earshot of the gun that they should seek cover. Training on how to use pepper guns can be built directly into the training videos.

I can think of a few scenarios here—where a shooter tries to maneuver around this. Maybe he tries to remove all of the pepper guns before opening fire. But guess what—the moment he does, the alarm sounds. And if they’re as numerous as fire extinguishers, he won’t be able to remove them all before getting stopped. Maybe a shooter realizes that pepper guns are being used to stop him—and he has to wear a mask. Okay—but that mask is yet another barrier in the way of becoming and acting on a shooting impulse. And masks can restrict movement and impede vision. So the shooter will probably be less effective. And wearing or even carrying a mask will make the shooter easier to spot, easier to avoid and get away from—and ultimately easier for first responders to identify in order to stop.

Pepper guns also serve another purpose: reducing fear. In the same way that having an alarm system at your house reduces your fear of a break-in, or a security guard reduces fear of a robbery, a defensive device can put people’s minds at ease that even if something were to happen—they’d be ready and able to stop it.

Physical Security

But let’s say you get advance warning. You have all of the training in the world. But there’s no emergency exit to get away through. Or the door you’re trying to lock behind you won’t lock. Or the pathway is blocked. What then? We can reduce the impact of mass shootings by creating safer spaces. Spaces that have safety built in. Because all of those scenarios I just mentioned—that’s exactly what faced students at Virginia Tech in 2007.

After that incident, doors changed. Back then, there were push-bar metal doors—with two different bars on each door that had a gap—making it possible for the shooter to lock his victims in by chaining them together. You won’t see too many doors like that anymore. They’ve been replaced with push-tab double doors. They have the same quick-release function, but there’s nowhere to loop chains. That’s progress. But it didn’t stop there. Because sometimes the problem is locked doors—and sometimes the problem is doors that don’t lock. Virginia Tech suffered from both issues. Students and professors found themselves in classrooms with doors that just couldn’t be locked from the inside. So the shooter just strolled in and out as he pleased. After Virginia Tech—locks changed, too. Now, doors that can lock from the inside are part of the safety standard at universities.

It’s amazing just what a difference a little lock can make. If you remember, the same change happened after 9/11. Airline cockpits started locking their doors. Offices can do the same, today. And more. Like removing dead-ends in buildings. A dead-end is any space where there is just one way in and out. A classroom on the 3rd floor has only one way in and out. A movie theater with stadium seating only has exits in one direction—towards the screen. So, when the shooter in Aurora, Colorado opened fire, there was nowhere for those in their seats to run but up against a wall. And a bathroom in a nightclub—only has one way in and out. So, when the shooter at the Pulse Nightclub took hostages in the bathroom, they were trapped.

A lack of exits doesn’t just keep potential victims locked in—it also limits options for police and first responders. Imagine if there was a door between classrooms, or emergency exits at the top of movie theaters, or an emergency exit in the bathroom at the Pulse Nightclub. How many lives could have been saved? Yes, more doors means more points of access to patrol when preventing thefts and robberies, but patrolling emergency exits isn’t rocket science. We do it all the time. But much of this design is based on how fires operate—not how shooters do. Architects, building owners and construction companies should consider ways that they can more strategically lay out their existing fire exits, and when necessary, create a few more. This could speed all types of evacuation scenarios, not just those at the pointed end of a gun.

And while we’re on physical security—there’s something else that schools and businesses should consider: ways to keep firearms out of the building. Metal detectors.

This is a controversial subject. Lots of people bristle at the idea of kids walking through metal detectors to make it to 2nd grade. But nobody seems to mind when those same kids are walking through metal detectors to get on an airplane, to see a concert, or visit Disney. Security screenings happen because they work. They keep people safe—not only by stopping weapons, but by discouraging would-be attackers from trying it in the first place.

At the very least, factories and schools should consider adopting them. Because far too many active shooter events could have been prevented if firearms were stopped at the front door.

The cost of this might seem high. After all—there are about 130,000 schools in the United States: that’s public and private. That’s a lot of security. But when you look at how much the government spends each year on each student, the cost of having four or five metal detecting units per school isn’t much at all. Consider this: each year the average state spends $10,700 on each student. Since each student spends on average about 4 or so years at each school—5 years in elementary, 3 in middle, 4 in high school—each school in total gets about $46,000 for each student during the duration of their education. What’s the cost of metal detectors at each school? About $16,000 a year. So—for less than a quarter of what it would cost to add just 1 extra student to your school each year, you can install metal detectors. Metal detectors that—if they had been there over the last 15 years—could have saved 62 lives. But that doesn’t mean the schools have to pay for it. Parents could band together. If each school has on average about 1,000 students, then for little more than a dollar a month, every parent could help pay for the security to keep their kids safe. Doing this would instantly reduce the number of active-shooter casualties by 9 percent.

The cost-benefit analysis is just as compelling for factories. There are 12.3 million manufacturing employees. The average number of employees per establishment is 36 people—so you wouldn’t need as many metal detectors. Each metal detector package comes with two wands—those hand-held metal detectors that can be swept over people. So let’s say each establishment buys two units and four wands. That’s a cost of $7,000. But that’s the upfront-cost. If we assume each unit lasts about 5 years, that’s a cost per employee of just $38 a year. Or $3 a month. For the cost of $3 a month per employee, we could effectively end active-shooter events at these facilities. This could reduce the total number of casualties in active shooter incidents by 11 percent. If the next 15 years are the same as the last, we could save 77 lives.

Wait! Wait, I hear you saying: there’s a problem with this cost analysis, and there is: it only covers the cost of the technology. Not the security staff to screen incoming students and employees. Yes. Yes, that’s true. Partly this is because many schools and businesses already have some form of security who could very capably run this equipment at the start and end of the day. But I know what you’re saying: what about the institution that doesn’t have on-site security personnel? What about the cement shop in Cupertino, California? The one with just 36 employees? Will they need to hire a whole new employee just for security? And is one employee enough to hold back a shooter—if there is a shooting situation?

Well, first of all—one security staff member is better than none. And getting a shooter to reveal their intentions at the door is much better than a shooter being able to trap coworkers deep in the building. But—but I hear what you’re saying. This is going to wreak havoc on our cost calculation.

In that first analysis, if a small shop of 36 employees gets one metal detector—technology only—it’ll cost each employee about $1.62 a month, every month, for 5 years. But if on top of that you need to hire a security staffer…it’ll cost each employee $95 a month, every month. That’s way more expensive.

But—but there is a technology solution. An absolutely brilliant one. And it could work for schools or manufacturing facilities alike. It’s called the automated security door. Well, two doors, actually.

You know that space you find in some office buildings between the door to the outside and the door to the inside—that empty vestibule that keeps the cold wind or the humid air out? Well, the idea is this: you arrive at work and walk through the first door. Inside that glass box space is a metal detector. The door you just walked through closes and you walk through the metal detector. If the metal detector doesn’t detect any metal, a green light flashes and the second door—the door to the inside—this one unlocks and you are cleared to step into work.

If you don’t pass the metal detector, a notification is sent to a designated staffer, who watches you remove metal like keys or phones from your pocket and place them on a tray. You go back through the metal detector and if it flashes green, you can enter the building. Exiting is a much more straightforward process—but still one that uses the double doors to stop intruders from getting in.

The system uses smart algorithms, cameras and machine vision to automate the process. And the glass is completely bullet proof. It’s more expensive than the average metal detector, but it doesn’t need to be manned—and it can operate 24/7 for 10 to 15 years. The whole unit costs between about $40 and $70,000 depending on how many lanes and the layout. But it certainly helps our calculation.

For that 36-employee workplace—rather than paying $95 a month for a metal detector and full-time security staffer, each employee under this security system would only need to pay about $10 a month. That would mean security cost amounts to literally 0.26% of each employee’s annual salary. Here’s what that looks like on a graph:

Taken together—just this small cost of a little more than a dollar a month per student, and $3 to $10 a month per manufacturing employee, we could reduce total active-shooter casualties by 20 percent. That's pretty dramatic—and I think well worth the price. Even if the employee or the parent is paying for it out of their own pocket.

But of course—they shouldn’t have to pay for it out of their own pocket. Security should be the responsibility of the institution. So, what’s this cost mean to them? Well, it amounts to even less for the average manufacturing corporation. Using aggregate numbers about the industry, I calculated that it would cost the industry just 0.07% of their profits. For a sense of what that means:

The bestselling car in the US is a Toyota Camry — and it costs $23,000. If we imagine the profits of the manufacturing industry as a Toyota Camry, 0.07 percent would be $16. That’s the price of a single floor mat on eBay. If you can buy a Camry, you can afford a floor mat. So—can the industry afford it? Yes, they can.

All of this is possible today, if we only think about ways we can make our spaces safer. Safer for learning. Safer for working. Safer for living. just imagine how much safer you would feel entering these institutions knowing that everyone else entered securely.